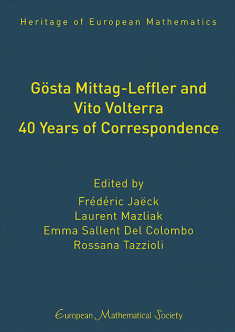

Ce livre contient la volumineuse correspondance échangée entre le mathématicien suédois Gösta Mittag-Leffler et son collègue italien Vito Volterra sur une période de près de quarante ans entre la fin du 19e et le début du 20e siècle.

La relation entre les deux hommes s'est développées pour des raisons aussi bien personnelles que scientifiques. Mittag-Leffler a rencontré Volterra pour la première fois quand il était un brillant jeune étudiant d'Ulisse Dini à Pise. Bientôt captivé par la créativité et les compétences du jeune homme, il décida de devenir son mentor. Étant lui-même au centre d'un réseau scientifique étendu, Mittag-Leffler présenta à Volterra les grands mathématiciens de l'époque, notamment des Allemands (Weierstrass, Klein, Cantor…) et des Français (Darboux, Jordan…). En quelques années, Volterra devint le mathématicien italien le plus en vue et créa son propre réseau de scientifiques dans toute l'Europe, et même aux États-Unis, qu'il fut l'un des premiers grands mathématiciens européens à visiter. Malgré leur différence d'âge, les deux hommes entretinrent une amitié profonde et fidèle et leurs lettres reflètent la diversité des thèmes de leurs échanges. Bien sûr, les mathématiques en étaient le premier sujet, et les deux hommes utilisèrent souvent les lettres comme première ébauche de leurs idées et leur destinataire comme premier juge de leur pertinence. Outre les mathématiques, les deux hommes ont également abordé de nombreux aspects de la vie privée et publique: mariage, enfants, vacances, politique, etc.

Ce vaste ensemble de lettres offre ainsi au lecteur un aperçu général de la vie mathématique à la fin du XIXe siècle et une appréciation de l'esprit intellectuel européen qui a pris fin, ou a tout au moins subi un tournant décisif au moment de la Grande Guerre. Les échanges entre Volterra et Mittag-Leffler illustrent comment l’analyse générale, en particulier l’analyse fonctionnelle, s’est considérablement accélérée au cours de ces années, et comment Volterra est devenu l’un des principaux leaders du sujet, ouvrant la voie à plusieurs développements fondamentaux au cours des décennies suivantes. Les lettres permettent de suivre la carrière institutionnelle et l'activité scientifique de Volterra et de Mittag-Leffler, qui ont partagé de nombreux détails sur leur situation.

Une longue introduction générale à la correspondance explique le contexte et les conditions dans lesquelles elle a été développée. De plus, les lettres intégralement retranscrites sont abondamment annotées afin d'offrir une image culturelle très étendue de la période.

Et en anglais...

Mittag-Leffler met Volterra for the first time as a brilliant young student of Ulisse Dini in Pisa. He was soon captivated by the creativity and the skills of the young man, and eventually became his mentor. Being himself at the center of a major scientific network, Mittag-Leffler introduced Volterra to the major mathematicians of the time, especially the Germans (Weierstrass, Klein, Cantor…) and French (Darboux, Jordan…). In a few years, Volterra became the most prominent Italian mathematician and forged his own network of scientists all over Europe, and even in the United States which he was one of the first major European mathematicians to visit. Despite their difference in age, both men developed a deep and faithful friendship and their letters reflect the variety of themes of their exchanges. Of course, mathematics was the most prominent, and both men often used the letters as a first draft of their ideas and the addressee as a first judge of their soundness. Besides mathematics, they also touched upon many aspects of both private and public life: matrimony, children, holidays, politics and so on. This vast set of letters affords the reader a general overview of mathematical life at the turn of the 19th century and an appreciation of the European intellectual spirit which came to an end, or at least suffered a drastic turn, when the Great War broke out. Volterra and Mittag-Leffler’s exchanges illustrate how general analysis, especially functional analysis, gained a dramatic momentum during those years, and how Volterra became one of the major leaders of the topic, opening the path for several fundamental developments over the following decades. Through the letters one can follow the institutional career and scientific activity of both Volterra and Mittag-Leffler who shared many details about their situation.

The four editors are all specialists in the history of mathematics of the considered period. An extensive general introduction to the correspondence explains the context and the conditions in which it was developed. Moreover, the original letters are annotated with a large number of footnotes, which provide a broader cultural picture from these captivating documents.